Thoughts on Phase Three: Amanda Brock, CEO, OpenUK

Key Findings

Executive Summary of Phase Three and Look back to Phases One and Two

The Economics of Open

- The Value of Open Source Software

- Measurement of the Value

- Estimating the value of open source software using number of contributors

- Estimating the value of open source software based on revenue

The Non Economic Values of Open Source Software

- Revenue and Transparency of Open Source Software Use

- Open source software and Collaboration

- Open Source Software and Skills Development

- Open Source Software and Security

Open Source Software for Sustainability

Opening Up the UK Energy Sector

Energy Sector Case Studies

- Icebreaker One

- Scottish Power

- ZTP

Healthcare Case Studies

- The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health

- NHSX

- Mindwave Ventures

- Digital Health and Care Wales

Acknowledgements

Methodology and End Notes

Contributors

Thoughts on State of Open: The UK in 2021

Amanda Brock, CEO, OpenUK

Amanda Brock, CEO, OpenUK

They said that the chances of anything coming from Mars was a million to one, but thanks to the open source software Apache Kafka data from holes drilled into Mars rock by the Perseverance Rover mission has come from Mars to our friends at NASA. I am super impressed with the rate of adoption of open source software on Mars. Earth needs to watch out!

In our pandemic world, OpenUK’s publication of Phase one of this Report, a mere 7 months ago feels more like a lifetime ago. We promised three phases and that the third phase would be: “Phase Three: Economic Analysis of Value generated by open source software”, a consideration of the economic value of open source software to the UK digital economy. Of course, we are delivering on that promise with the work done for this phase of the Report and with the help of Smoothmedia, have taken our survey outputs and collaborated through two workshops to evolve the theory of the economics of open source.

This will clearly need ongoing and concerted work and collaboration to evolve. We intend to conduct a second survey in 2022 and for this to become an annual activity for OpenUK. We will learn from the experience of the first and plan to collaborate with other UK organisations to find a broader pool to respond. We’ll also continue to evolve benchmarking metrics to support this. We expect to publish this in Q2 of 2022.

Our work on security has not made this Report, but will manifest in the announcement of Robert Carolina as our Chief Security Policy Officer and the creation of a Security Advisory Board for OpenUK.

However, in this Phase we focus on Values, including a whole lot more than economics. Instead, we want to share the Values, plural. We need to acknowledge the hidden values, around skills development, collaboration and environmental sustainability.

This leads us naturally into the OpenUK Sustainability policy and work that is being led by Cristian Parrino our Chief Sustainability Officer. This in turn leads us to the UK’s energy and healthcare sectors. Both of these sectors are rapidly immersing themselves in open source software and open data, with the Digitalisation Task Force and Icebreaker One taking a global leadership role in opening up energy, whilst the NHS across the UK shifts to a clear open first strategy.

Our contribution from these sectors begins a journey which is very clearly to be continued, gazing towards the lens of a future Carbon neutral or even Carbon negative UK, benefiting from open source software for sustainability. OpenUK will itself be leading on this as it hosts the Open Technology for Sustainability Day at COP26, to include a keynote by Lord Maude of Horsham.

“We strongly believe that open source powers innovation, and it gives us faster time to market and greater productivity. These benefits are not an automatic advantage of using open source software. We build our products on top of open source technologies, and we know that we only reap all of the benefits of open source if we contribute back to it”

Dr. Dawn Foster, Director of Open Source Community Strategy, VMware OSPO

“I wasn’t in open source for the first 20 years of my career, and I am sure that I would not have been as involved now if there weren’t things happening locally, and events happening in London. Having that kind of enthusiasm on the ground and a small handful of people to seed excitement has generated a pretty strong cloud and open source workforce here.”

Liz Rice, Chief Open Source Officer at Isovalent

“Filling open source leadership positions can be a challenge, so many employers are willing to be flexible about location in order to find the right person. My role is based here because I was the right fit for this role, and I live in the UK.”

Dr. Dawn Foster, Director of Open Source Community Strategy, VMware OSPO

“It’s very rare today that I come across skepticism about the idea of open source which I think is a big change from 20 years ago.”

Cheryl Hung, Engineer Manager, Apple Cloud

Key Findings

Phase Three Executive Summary and Look back to Phases One and Two

Dr Jennifer Barth, Smoothmedia

Dr Jennifer Barth, Smoothmedia

Diverse, global, collaborative and sustainable. The underlying ethos of open source software encompasses some of the most important aspects of society today.

When understood alongside the business benefits, these tangible and intangible values of open source software cannot be understated. To shed light on the important role of open source software in powering the UK economy, we embarked on three phases of State of Open: The UK in 2021 Research.

In Phase One, we took a baseline of existing literature and conversation, bringing the role of open source software to the forefront of digital innovation and breaking existing data down for the UK. Although few had focused solely on the UK, we drew on what we could, enjoying the collaboration of others working in this area to bring forward the central role that open source plays in our UK economy and lives.

Phase One brings to our line of vision how open source is a critical pillar supporting digitalisation in both the private and public sector across the UK. The Report allows all sectors of the UK economy to understand, plan and take account of open source software and its potential to enliven agility and innovation. It establishes the UK as one of the world’s largest contributors to open source software, in the top five for open source usage outside of the US and a centre of excellence in this area.

With that in mind, we are working to support and develop UK leadership in open source software, while collaborating globally and have additionally hosted our first two quarterly workshops with others to create real and effective benchmarking. The true extent of use and the productivity benefits of open source software remains elusive. The pandemic is changing the way organisations and leaders view open source, shedding light on its value and unique attributes in solving challenges. It’s a building block – on top of which we must invent and innovate to produce something new – and the grounds for a shift from competition building on ground zero to coopetition and collaboration on top of a shared codebase and processes. We see the growth of an entirely new industry model based on the sharing of intellectual property originating in diverse and global collaboration that has local impact.

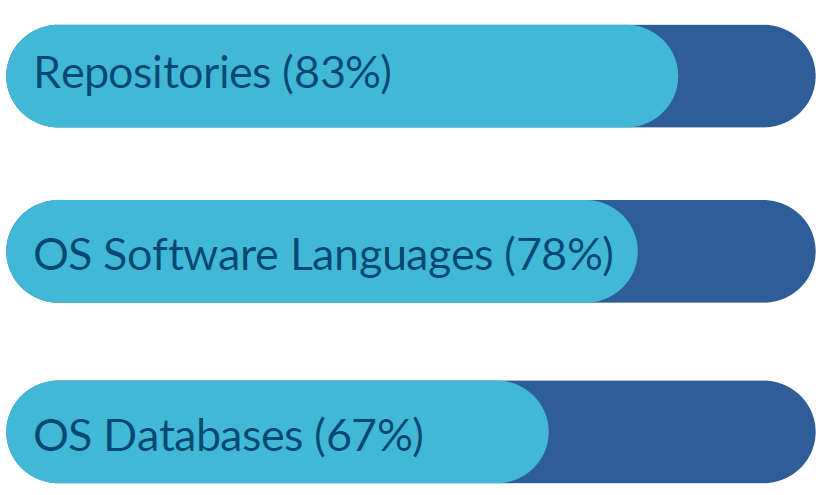

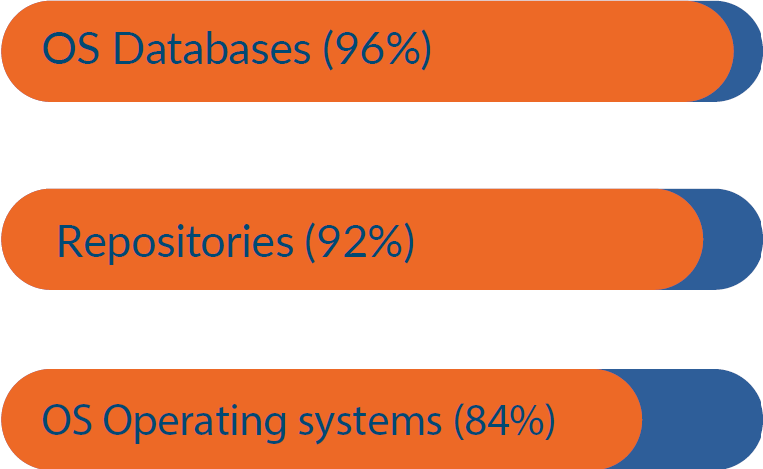

In Phase Two, we put the first of its kind UK-based open source software survey into the field of open source data. This has allowed us to better understand uptake, use, governance, security, recruitment and the future outlook for open source in the UK. An incredible 89% of respondents run open source software in their businesses. 64% of businesses in the survey experienced business growth in 2020 compared to 2019 and 48% report an increase in the use of open source software in that same period.

A focus on security and the growth of Open Source Program Offices (OSPO’s) highlighted in Phase Two reflect a growing need to create a formal engagement with open source software through good governance to ensure risk management within companies and the public sector. And, we found, adoption is not straightforwardly about cost savings. There is increasing importance placed on collaboration, skills development, quality assurance, transparent practice and sustainability as part of the extensive global impact. Development of open source software relies on collaboration and participation of communities of like-minded people. These in turn bring tangible benefits to business via network effects.

Such network effects are what we come to in this Report, Phase Three, the final of our three-part State of Open: The UK 2021 research. We return here to the importance of measurement, use and revenue to consider the broader impact of open source software on the discussion of environmental sustainability.

Our findings show that there is polarisation in the economy, with large firms and small firms being more active in the open source software sphere, while medium sized organisations remain more hesitant when it comes to engagement. In terms of 07 State of Open: The UK in 2021 Phase 3: The Values of Open collaboration and skill development, although the general patterns are the same across organisations of different revenue, the depth of engagement varies, with the smaller and larger firms making the most of the opportunities available.

Attempts to value the impact of open source software have tended to revolve around total cost of ownership, lines of contribution or number of engineers contributing to open source software, employment of people in the digital sector, software related patents or personal motivation. While measuring the value of open source software to the UK economy is difficult due to a lack of consensus on what should be measured and how as well as a general lack of data on the business case of the pervasiveness of open source itself, we sought new ways to do this.

New ways to measure the value of open source software need to be iterative and flexible. Rarely is there a large up front investment that depreciates over time as with traditional assets on a balance sheet. Instead, systems are built for their flexibility, agility and ability to flex and change as and when needed, ensuring system sustainability. Open source allows for such efficiencies and as such investments may be made incrementally, contributions follow a pattern where users evolve into contributors and people are motivated to work on projects and should be compensated for this work. This is a competitive, versatile and secure process that enables a culture of transformation. We need to understand and promote valuations that take these into account.

Our initial calculation based on the released work of the European Commission study, showed that the UK’s open source software contribution to GDP could be between £29.52bn and £43.15bn for 2019, based on the number of contributors. The UK’s position was established as number one in open source software in Europe and generally being the fifth biggest global contributor to open source software. As a huge part of the UK’s digital economy is reliant on open source, this speaks to the potential value of this contribution.

Alternative ways of calculating the value of open source software to the UK using the number of contributors, as discussed in Phase One, suggest that the impact is between £10.5bn and £18.44bn for 2019, while using GDP, in 2019 it is likely to be between £11.47bn and £16.74bn. Phase Three presents first an update of the latter for 2020, where the band is estimated to be between £11.4bn and £16.6bn, and secondly, by using the OpenUK survey the research estimates a contribution to the UK economy of £15.7bn for 2020 for UK businesses, expressed as direct cost savings. This value may not capture everything as indicated in the potential values discussed in Phase One, but it goes a long way to solidifying the economic impact and opening up the conversation to consider all that is not captured in this number. Very tentatively, considering the additional benefits to businesses on top of cost savings, we estimated that the total potential value for businesses in the UK is up to £46.5bn for 2020, if we were to include collaboration, skills, and quality of code, aspects this work strives to consider and value. However, further research is required to be certain about these estimates, as the small sample size reduces confidence in the findings.

Our findings in this Phase Three Report illustrate that there is overall awareness of the benefits to business. Organisations that are strong in running and contributing to the development of open source software are also collaborative, ambitious and see beyond cost saving to reap the benefits of skills development. The case studies across the financial, research and education, charitable, energy and health sectors, are woven throughout the State of Open suite of Reports evidence growth in open source software use and development. In some organisations the use is not ubiquitous but there is a concentration in a particular project, offering a solution to a previously unsolvable challenge. This use is extending to a culture of creation, development and productivity amongst those involved and changing organisational approach to digitalisation and collaboration. Yet still, it is difficult to measure the impact.

If organisations are not aware that they are using open source software or the full extent of its use, it is not possible to understand how much it contributes to their revenue and growth. They may also not be able to benefit from its true values including skills development and collaboration, transparency, greater security and risk awareness, agility and speed. In many cases it is a submarine under the digital economy. The particular role of reuse and recycle, an area which provides cost benefits, investment and environmental sustainability is considered in this Report in further attempts to measure the value of open source software to the UK in its move towards net zero.

Going forward, our Report has emphasised the need for a two-fold strategy if the UK wants to maintain its competitiveness as a digital economy leader.

Businesses need to become aware of the opportunities for skills development and the growth open source software offers and be encouraged to interact more. Additionally, there needs to be an understanding on how open source fuels the UK economy, by coordinated effort from not only private and public sector business, but by active policy that supports this aim.

Economics of Open

The Value of Open Source Software

Following the two previous Report Phases, State of Open UK: The UK in 2021 Phases One and Two, Phase Three focuses on the values including the financial value of open source software. This follows a financially difficult year in the UK, which saw a dramatic change in the way businesses, society and the government operate. The ability of organisations to “go digital” at pace and efficiently is a decisive factor today for success in this context. Those who tend to be best placed to do so are organisations with sufficient resources and those that think smart about change. Open source software is not only at the core of every technology used around us, like gravity, but is also a valuable asset for organisations that want to innovate, and to develop skills and technologies in a collaborative, low barrier to entry spaces. This need becomes understandably more pronounced in periods when the economy has experienced a shock and financial or human resources are stretched.

Despite Government commitments to increase uptake of open source software among public and private organisations, over the last decade in the UK, there is no consensus on how open source software and its adoption is measured at macroeconomic (economy) or microeconomic (firm) level. This makes comparison and benchmarking of the achievement of this difficult. This Report aims to set the foundation for committed adoption and utilisation of open source software in the long term and the intention is that it will be reviewed and updated on a regular, at least annual, basis.

The intention is for the Report findings to complement and inspire further understanding and research.

“In terms of enterprise adoption and platforms, it’s so massive. I know enterprises that have enormous adoption, like 80 plus percent and others with almost 0. It’s very hard to give you a number. It very much depends on the enterprise that you’re talking about” –

Cheryl Hung, Engineer Manager, Apple Cloud

Measurement of Value

Measuring the contribution of open source software to an economy cannot be done using conventional methodologies. As pointed out by Will Page in Phase One, this is true for music and other digital technologies as well as for open source software. Coupled with its fast-paced growth and role across the entire digital economy, it is impossible to fully capture that value. There is very little data available. Due to the commercially sensitive nature of revenue responses in our survey (despite being anonymous), the number of responses to q 17a (What percentage of your revenue comes from open source software) was too low to be able to report raw findings. This is indicative that although businesses are using open source software, they are not yet fully aware of its quantitative contribution to their business.

Some companies put a ton of effort into open source and they get a lot back from it, but it’s hard to measure. It’s like how much

benefit do you get from donating to charity, like there are good things about it, but it’s very hard to measure the impact of it.Cheryl Hung, Engineer Manager, Apple Cloud

The challenges in finding the financial value of open source software to any economy and in particular, to the UK economy are set out below.

Information about participation in the production of open source software is publicly available, but the actual use of open source software by all kinds of organisations (how much they actually use or rely on it) is less transparent. Many who have sought to value this have considered lines of code contributed to measure value, but concerns have been raised about whether all code/ contributions are equally “useful” in the production/ operation of business and services. This is further complicated by the lifetimes of each contribution that are not known, thus making it impossible to estimate their value, because they cannot be considered an investment or intermediate consumption.

The commonplace developer practise of having a single account (and ID) on GitHub or other repositories, with an associated email address, used by them to contribute to all projects despite their contributions potentially being made under a number of personal hats, adds further to this uncertainty. Certainly it calls this measure’s accuracy into question as being a 09 State of Open: The UK in 2021 Phase 3: The Values of Open solid basis for defining the source of contributions and level of contribution on behalf of any entity.

Using a more typical economist’s methodology for finding the value of an economic activity to an economy, such as using national statistics on own production of software, is also challenging. When applied to calculate the contribution of open source software as own account software, it simply fails to capture the development of open source software. It only captures purchased software and own account software with an economic owner. Open source software is excluded from the system of national accounts (the standard for country GDP reporting) because it does not meet the criterion of economic ownership.

The OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2020, an authoritative text on the global digital economy, does not suggest any method of measuring the economic value of open source software to the digital economy. It does however include a brief discussion of open data, and more recently data markets and data portability, and their indirect value, in reference to enhancing data access and sharing.

When the OpenUK survey was designed, the aim was to fill in this identified gap in essential knowledge.

Two questions in the survey, in particular, q 16 and q 17,were designed to gather data to help calculate the financial value of open source software for UK businesses. The process is outlined below.

First, the boundaries of revenue in the survey questions mean that the value is conservatively calculated with a maximum (sum of the upper band) and a minimum (sum of the lower band), by company size (small, medium, large by number of persons employed). The minimum band for the lowest category of revenue (under £249k) can be defined at £1 (which is extremely conservative), and the band is also extremely conservative at £50m and £1.

The findings from q 7 (“Does your business – option “contribute”) by business size (small, medium, large by employed numbers), are applied to match not only the size of BEIS businesses, but also to ensure that this considers organisations that actually contribute to open source software.

Finally, the sums are weighted against BEIS data by revenue and company size, to make a cautious estimate (within a band) of the possible contribution to the UK economy.

The main issue faced was that the usable answers to calculate value using this process in practice were low. In the sample, 82 answers in response to revenue, were “prefer not to say.” This reduced the sample size for sectoral analysis by almost a third. This indicates that businesses are in fact using open source software but are not fully aware of its quantitative contribution to their business. As a result, OpenUK had a small sample of organisations that are unrepresentative of the economy, as those that responded are not the typical UK business. Future surveys will take account of this to alleviate the potential bias.

To resolve these issues and better understand how it would be possible to find an economic value for open source software anywhere in the world as well as in the UK, OpenUK has engaged with multiple stakeholders and so far has organised two workshops. These take place on an ongoing basis quarterly and are a forum to discuss the issues that come up when attempting to value open source software. The workshop discussions have acknowledged and confirmed the universality of the difficulties currently faced in calculating a value for open source software. This has cemented the determination to take on the challenge.

Stakeholders expressed the view that although open source software could reduce fixed costs for technology, it may understandably increase their labour costs, particularly where there has been digitalisation of a business. This discussion highlights an urgent requirement for the UK economy across all sectors: businesses need to become aware of and be included in digital transformation and understand the role and optimisation requirements of open source software in this process.

As business experience during COVID-19 demonstrates, digitalisation of business interactions has accelerated and deepened. By educating non-tech sector businesses in the potential benefits of open source software within the existing digital infrastructure and services, their ability to leverage that engagement increases, allowing them to generate financial and social value. As this evolves it will be possible to have a clearer picture of business users of open source software.

Where organisations are not aware that they are using open source software, they are unable to either measure it or understand how much it contributes to their own revenue and growth, and particularly will not benefit from the added values so central to open source software. Skills development, collaboration, transparency, increased security and risk awareness and agility and speed, all discussed later in this Report, are amongst them.

Reuse and recycle, an area of benefit which provides not only cost savings but also environmental sustainability, is considered below in calculating the values of open source software.

Estimating the value of open source software using number of contributors

Phase One utilised preliminary findings from the, then unpublished, European Commission study on the “The impact of Open Source Software and Hardware on technological independence, competitiveness and innovation in the EU economy”, to provide estimates of the value of open source software to the UK economy. This study, now published, looks at the regulation, policy and progress of open source software in 2018 for the EU-27. The study does not offer separate estimates for the UK, although it is included in some calculations which are analysed primarily in terms of policy and government initiatives.

It estimates that companies located in the EU invested around €1 bn in open source software in 2018. This was calculated to result in an impact of between €65bn and €95bn (£60.9bn and £89.05bn) to the European economy. Drawing on the calculations of the European Commission study, in Phase One OpenUK attempted to update these results for 2019, based on the number of contributors- a common method in this space, but as explained an imperfect one.

The result was that if 260,000 contributors could lead to an economic impact of open source software between £60.9bn (€65bn or $77.8bn) and £84.15bn (€95bn or $113.7bn) in Europe, then 126,000 contributors in the UK in 2019 can lead to an impact between £29.52bn and £43.15bn, on the condition that individual contribution did not change from year to year.

“Some of the larger tech players have been active in the open source space, in platforms, things like that. I think they’ve contributed and sponsored it and made it far more normal and accessible.”

Carolyn Jameson, Chief Trust Officer, Trust Pilot

At the time of writing of the Phase One Report, this was a best estimate given the data available. Currently there are no reliable data to draw our estimations forward using this method. This is indeed believed to be a potential value of contribution based on the European Commission work, but continued work and evolution of methodologies may create greater transparency of actual usage and build greater consensus on forms of measurement.

Aside from the lack of data, macroeconomic modelling based on contributors suffers from technical and conceptual limitations. The authors of the study acknowledge that there is a risk of over and under estimation of the contribution given the aggregation method used. Additionally when considering other data in the study, the dependent variables, such as R&D, are not open source software-specific. They are general indicators of economic activity, competitiveness or innovation, which may reduce the power of conclusions drawn because they capture aspects beyond that which are relevant to open source software.

The study offers a very detailed account of the policies and opportunities for development of open source software in different EU countries, pointing out the differences in adoption of technology. It is an important resource to understand this in the EU and consequently to build understanding in relation to the UK.

“Comparing modern and legacy infrastructures is difficult – sometimes the IT infrastructure is so new and so different. It is also difficult to compare one company with another. Total cost of ownership no longer works.”

Carlo Daffara, CEO and Co-founder, NodeWeaver

Estimating the value of open source software based on revenue

Following similar assumptions to those in OpenUK Phase One in respect of revenue and using the survey findings for q 7, an alternative value of open source software is calculated for UK businesses. This is the most straightforward way to capture the broader effect of open source software in the economy. It does not look at the number of contributors, lines of code or projects, as a unit of measure for value as these are difficult to accurately capture and involve too many assumptions. At the same time, there is greater certainty that the findings are not skewed towards larger organisations in the tech sector.

Using IBIS world data for the UK, the value of software development is estimated to be £24.9bn in 2020. The OpenUK survey indicates that 63% of companies contribute to the development of open source software – close to the 60% figure for 2020 quoted by Daffara (2020), leading to a value of £15.7bn in terms of revenue for UK businesses in 2020, due to software reuse cost saving. The OpenUK survey respondents emphasised the importance of cost saving when choosing open source software and with the UK economy continuing to be in recovery from the impact of the pandemic, this is a significant finding.

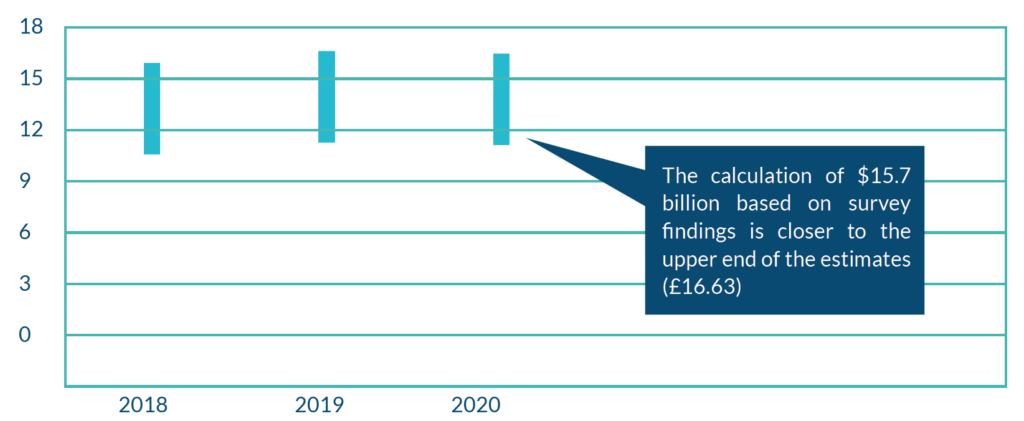

The base value for 2020, when juxtaposed with the estimates in Phase One, shows that it is quite accurate. Phase One presented estimates for the contribution of open source software to the UK economy in 2018 and 2019. ONS preliminary estimates for the ICT sector growth are that it declined in 2020 by 0.7%, making our estimate for the open source software 2020 contribution to the UK economy between £16.63bn and £11.39bn, drawing from Phase One estimations (Fig. 1). To some, this modest decline may appear counterintuitive given the general good health of the sector, however it is expected as it captures early recruitment and transition bottlenecks as a result of the pandemic in 2020 – see below findings on recruitment. This is a very small decline compared to the shock to the UK economy in 2020.

“There is a general mass digitialisation trend towards cloud hosting and web services which has been growing over a number of

years. In parallel, it is feasible that the same upwards trend is also being applied to the adoption of open source technologies”Leanne Kemp, CEO & Founder, Everledger

Figure 1

Open UK Phase 1 and 3, estimate bands in £bn

The value presented above does not capture the value generation for the more complex benefits from the use and development of open source software for an organisation. Cost savings are not the only benefit that open source software brings and this is precisely what this research has worked to make visible. Value-enhancing aspects of open source software are not fully accounted for in business statistics like skill development, collaboration and ensuring the high quality of the code add significant intangible benefits to a business. They enable businesses to engage directly in specific R&D with reference to open source software, build in-house software expertise, and avoid the risks associated with problematic code, as they have more control over its quality. These additional benefits add value to a business by strengthening its organisational capital and as such they formed the main pillars around which the survey was designed.

Drawing from the base value calculated above (£15.7bn) and the findings of q 8, the potential monetary value of collaboration is estimated at £11.3bn, the potential monetary value of skill development is estimated at £10bn, and the potential monetary value of high quality code is estimated at £9.5bn for businesses in the UK for 2020. This brings the total potential value for businesses in the UK up to £46.5 bn for 2020. This is a very tentative estimate as these pillars (collaboration, skills, quality of code) cannot be easily and fully captured by a small scale survey, because often they depend on each other (therefore there might be some double-counting we cannot avoid in our sample).

Additionally, R&D, skills development through in-work training, and collaboration do not manifest their value to an organisation directly in the short term, as they can take years to show results. There is no standardised way to measure these as benefits to an organisation. Thus, the estimates above should be treated with caution due to the limited sample size of the survey and lack of complementary data on open source software used by businesses in the UK to have an alternative reliable benchmark. The value should also be understood in light of the high number of ‘prefer not to say’ responses in the revenue-related questions thus preventing a better-informed estimate.

These limitations are acknowledged, but equally, it is important to value these aspects of the open source software contribution to businesses, and further work is needed to be able to understand their exact impact on business value in the UK. A more targeted approach in survey design, for example one that aims to investigate specifically open source software use, collaboration, skill development, quality of code and how they affect revenue will be considered in further research alongside a broader and deeper response pool.

Those aspects that have become part of the calculation here are not the limit of possibility and further research and collaboration is needed to ensure all possible metrics for the value generation of open source are considered and represented.

The Non-Economic Values of Open Source Software

The values of open source software must be considered in the light of the benefits that open source software contributes to business.

Transparency of use and contribution to revenue, skills development, collaboration, greater security, and risk awareness all provide a path to discuss more nuanced benefits to business success contributed by open source software.

This is considered through the lens of business revenue based on the OpenUK survey.

“The more advanced users and enterprises, who are pushing the boundaries, get involved because they want to be able to influence the roadmap and be part of that community, to make sure that the projects are healthy and long lived, and that they can continue to rely on them. At a level it’s everybody contributing into the same pot, and then that rising tide floats all the boats scenario. There is a little bit of prisoner’s dilemma, like, I have to be in it, because if I wasn’t in it, I’d be out of it. But it all works out to the good.”

Liz Rice, Chief Open Source Officer, Isovalent

Revenue and Transparency of Open Source Software Use

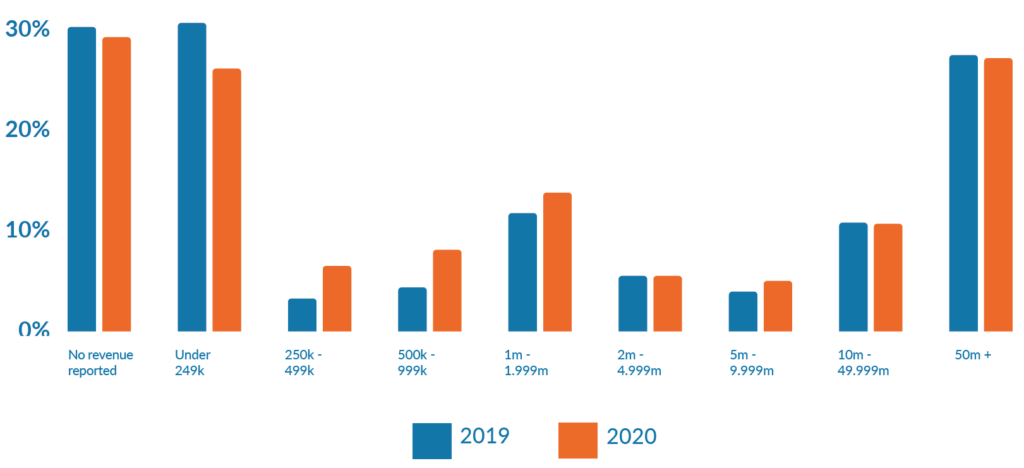

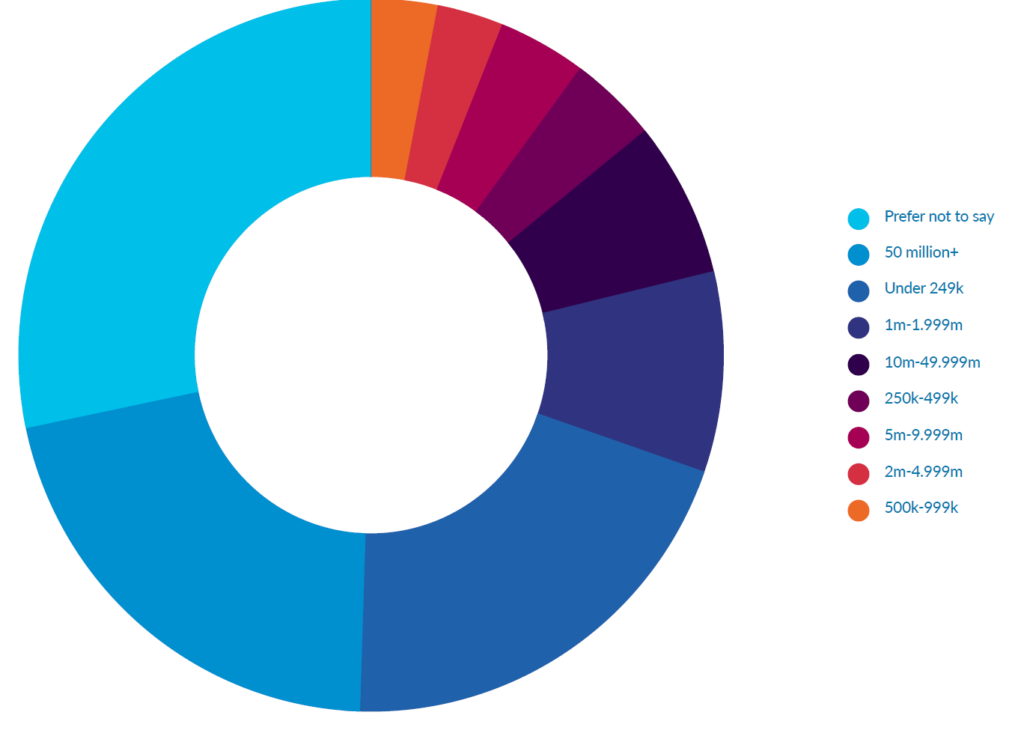

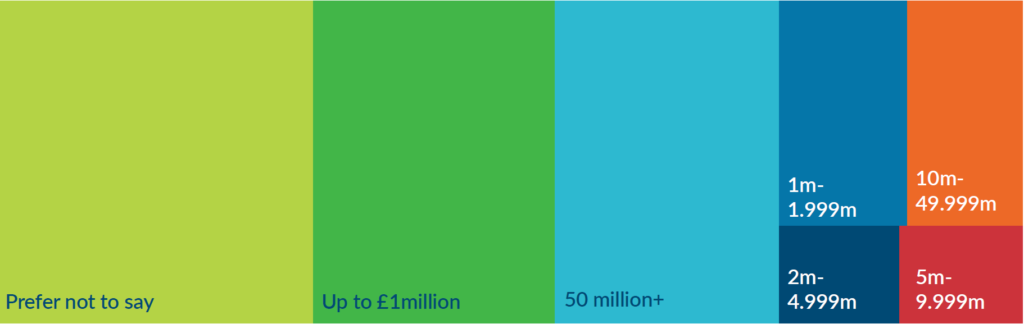

The respondents of the OpenUK survey span the entire spectrum of business revenue bands, with visible polarisation: organisations with revenues under £249 thousand in 2019 (30%) and 2020 (26%) and organisations with revenues in excess of £50m (27%), both in 2019 and 2020, make up the larger groups. Notably 30% of organisations 2019 and 29% in 2020 did not report any revenue (“Prefer not to say” option).

Figure 2

Q16. What was your business revenue in the following tax years?

In State of Open: The the UK in 2021, Phase Two, UK Adoption, respondents were asked to identify how much of their revenue was generated using open source software (any type) q 17.

This is a tricky question to answer, but must be considered. Respondents indicated cost saving is one of the main reasons why their organisations use open source software. As a consequence of this cost saving goal it would be a reasonable assumption that organisations would know how much value they have benefited from. This was however not the case.

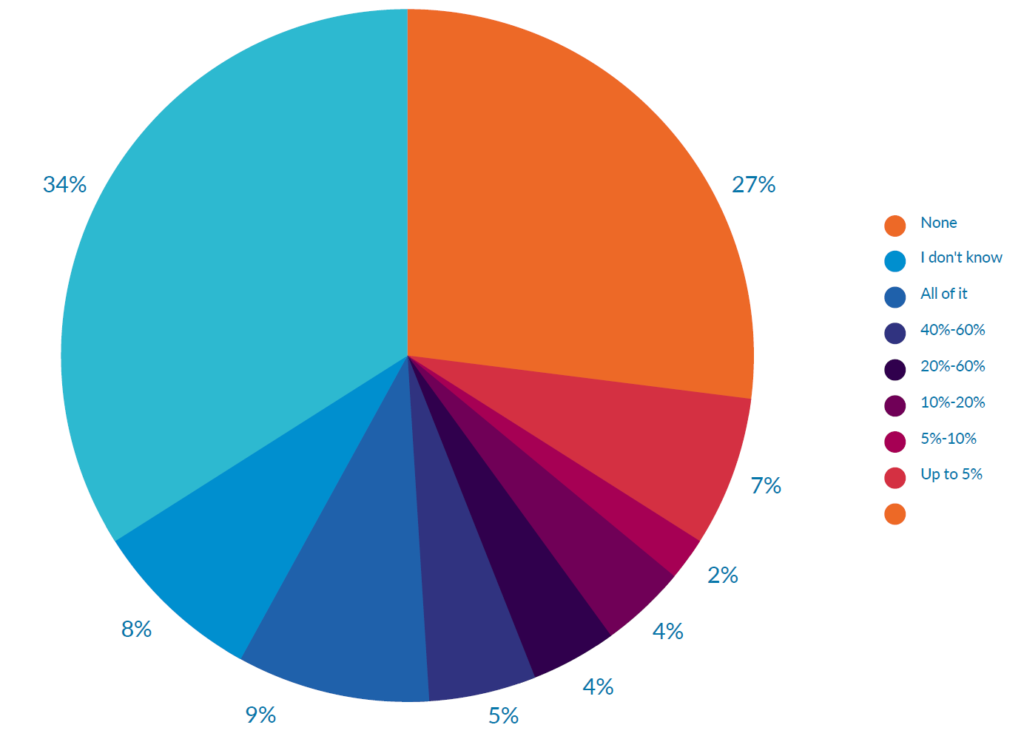

Figure 3

Q17. What percentage of your business comes from open source?

Approximately one-third of the respondents (34%) answered that they don’t know how much of their revenue comes from open source software, while 27% responded that none of their revenue comes from it. This points to two important issues. The first one is that there is a lack of suitable, standardised measurement in organisations to understand how much they benefit from using open source software directly in their operations.

The second one is that approximately 1 in 5 organisations does not deploy open source software as part of their services/ products to their knowledge, but this does not mean that they are not using it internally. Both issues are expected, given the diversity of the UK economy, but going forward a service-based economy, such as the UK, needs a much better understanding and embeddedness of open source software to achieve cost savings.

Aside from these groups, next were those in the extreme in responses: those that get up to 5% of their revenue from open source software (7%) and those that get more than 60% of it from open source software (9%).

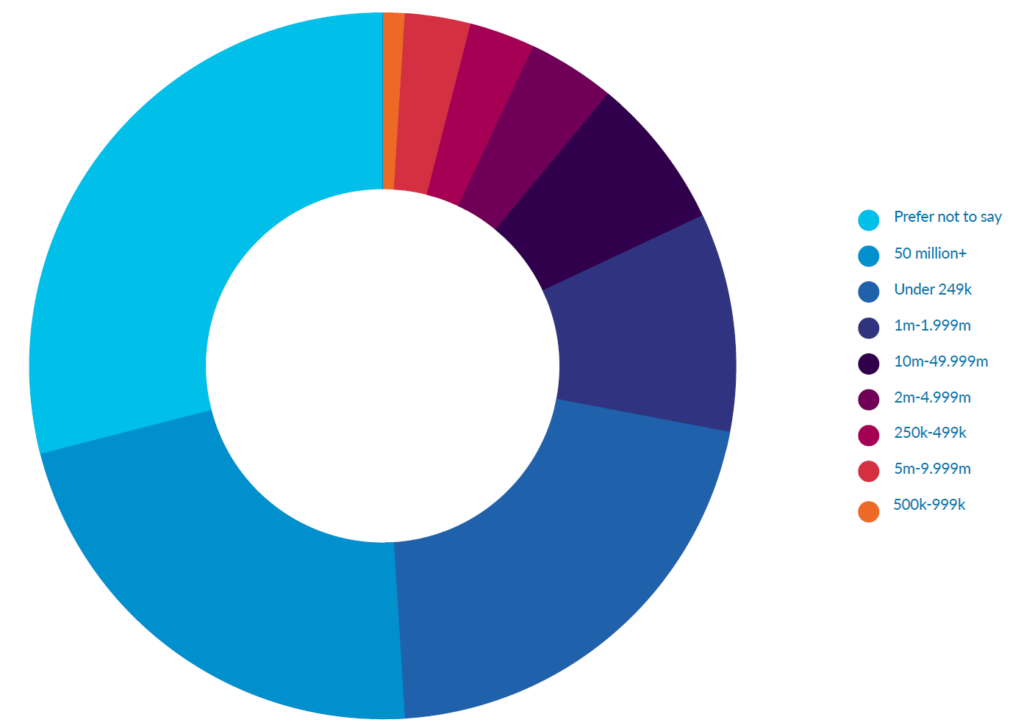

In terms of revenue the distribution of organisations that run open source software software and contribute to its development is comparable (Fig. 4-5).

What stands out in both cases is that the largest groups that contribute to open source software development are organisations with revenue above £50m (22%) and up to £249k (21%), as is the case for the largest groups that run open source software, with organisations with revenue above £50m (21%) and up to £249k (20%). This could indicate that those able to embed open source software in their operations and business model tend to be either small capitalisation firms that need the flexibility open source software offers while they grow to create cost savings, or larger firms that have sufficient resources to overcome issues that could appear when dealing with legacy systems.

Figure 4

Run open source software revenue

Figure 5

Contribution to open source software by revenue

Figure 6

Technologies used by organisations that up to 5% of their revenue comes from open source software

Technologies used by organisations that more than 60% of their revenue comes from open source software

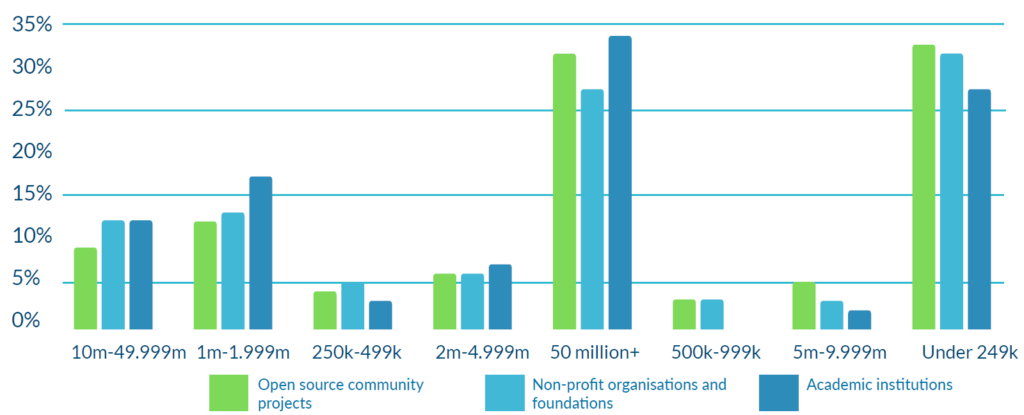

Open source software and Collaboration

Collaboration is at the core of the development of open source software. In Phase Two, collaboration was reported by respondents as the most important benefit after cost savings. From the organisations that prioritise collaboration, 26% have revenue below £1m (20% with revenue up to £249k), and 20% more than £50m (Fig. 7).

This finding stresses the importance of collaboration in early stages of the development of an organisation, as well as its importance for larger organisations that want to stay relevant and at the forefront of technological advance.

Figure 7

Collaboration as a priority by revenue

The three most popular collaboration partners in the survey were open source community projects, non-profit organisations and foundations, and academic institutions (Phase Two finding). Fig. 8 below demonstrates that the group that engages least in collaborations is organisations with revenue from £500k to £999k, while there is high collaboration intensity for organisations in the lowest and highest revenue groups. Low revenue organisations could be driven by the need to access knowledge and expertise that would not be otherwise available to them, for larger organisations a possible reason would be to remain innovative and push the frontier by accessing a larger pool of creativity.

Figure 8

Collaborations by income

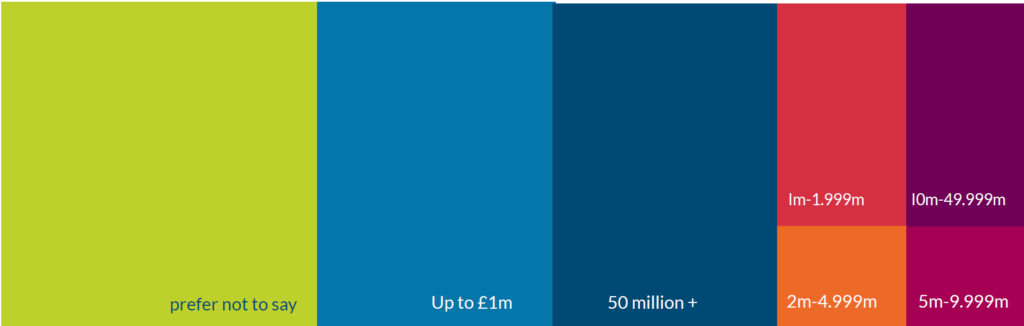

Open Source Software and Skills Development

Skills development is also one of the main benefits identified by survey respondents. Specifically, and echoing the findings above, out of those that see skills development as a top priority, 23% are organisations with revenue up to £1m and 22% organisations with revenue above £50m. This is an indication that smaller and larger companies compete for a very similar labour pool in the UK market as is seen in the discussion of recruitment.

Figure 9

Skill development as a priority by revenue

Skills development in ICT sectors is crucial, but it does not happen in isolation. Harris and Moffat (2021) have found that at times of crisis ICT jobs are less affected by adverse economic conditions in the UK, as companies invest time and effort in employee training and skills development, making them an asset for the organisation. As such, even at times of economic downturn, companies are less willing to let skilled IT professionals go.

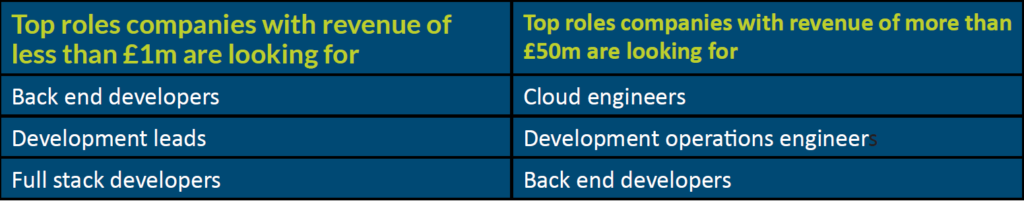

Companies with revenue of less than £1m lead recruitment for roles associated with open source work. 40% are planning to hire in the next 6 to 12 months back end developers, development leads, full stack developers, development operations engineers, front end developers, cloud engineers and project managers, while companies with revenue of more than £50m plan to recruit cloud engineers, development operations engineers and back end developers (see Figure 10).

Figure 10

According to Tech Nation and the Government’s Digital Economy Council, 10% of all current UK job vacancies are for tech jobs, higher than the current levels of employment in the digital sector (9%).

Open Source Software and Security

Phase Two demonstrated that most companies surveyed had adopted security provisions (q 14). In terms of revenue, the most popular protection among all groups of revenue were i) having a security policy (a definition of what it means to be secure for this system) and ii) having support for SSL/TLS on website, downloads, and infrastructure.

Out of those organisations that have a security policy 30% have revenue over £50m and 16% less than £1m, while out of those that have support for SSL/TLS on website, downloads and infrastructure 22% have revenue over £50m and 25% less than £1m.

No specific pattern was evident in the type of security provision between companies that earn a high proportion of their revenue (60% or more, or all of it), and those that do not, or earn a small proportion from open source software.

Finally, more organisations with revenue of less than £1m report the pandemic outbreak led them to increase use of open source software (32%) as opposed to organisations with revenue of more than £50m (26%).

Open Source Software for Sustainability

Cristian Parrino, Chief Sustainability Officer OpenUK

Cristian Parrino, Chief Sustainability Officer OpenUK

Sustainability is the challenge of our time: increased inequality, deepening social and financial exclusion, climate change, air, land and ocean pollution…the ecosystem breakdown that can lead to pandemics. These problems are connected and share the same root cause – an economic model which is relentless in its pursuit of growth at the expense of people and planet.

In 2015, the United Nations published the Sustainable Development Goals as its blueprint of 17 interlinked global goals to tackle this generational challenge, intended to be achieved by 2030. The transformation required isn’t just about decarbonisation, it’s about a systemic change which begins with shifting to an economic model that prioritises prosperity over growth.

Prosperity, as Kate Raworth defines it in her book Doughnut Economics, is the aim of meeting the needs of all people within the means of the living planet. Doing so is about ensuring that a social foundation is met for people across health, education, income and work, peace and justice, political voice, social equity, gender equality, housing, networks, energy, water and food. At the same time staying this must stay within an ecological ceiling that protects our planet from climate change, ocean acidification, chemical pollution, freshwater withdrawals, land conversion, biodiversity loss, air pollution and the depletion of the ozone layer.

Given the complexity behind this transformation, it is imperative that the open source principles of collaboration, decentralisation and collective equity, as well as the application of the fundamentals of open technology (hardware, software and data) being transparency, circularity and accessibility, play a central, enabling role.

We therefore need to begin measuring the value of open source not just in economic terms, but also in societal terms.

This must start with how we design solutions. The innovation frameworks used to develop services, products and standards – such as human-centred design and design-thinking – view people solely as individuals or even worse, consumers. They are about identifying individual user needs and how they can be fulfilled with more products and stickier services. The role of technology is primarily to drive operational efficiency, hockey-stick growth and profit.

These are designed from a position of privilege conceived by Ivy League academia, made popular by Silicon Valley and its VC’s, and turned into tool-kits by large consultancies, a majority of which are made up even today, of white, males of affluent backgrounds. The result of this is a self-perpetuating mechanism in which people aren’t considered in relation to their communities, and society itself isn’t considered at all. This can no longer be accepted.

Creating solutions that are fairer, more inclusive and that empower people, which design-out structural inequality, and are regenerative towards the planet requires a move towards a community-centred design model. This must be underpinned by cooperation, transparency, decentralisation and collective equity.

In other words…an open source software model.

This is the approach chosen by the City of Amsterdam as it emerges from the COVID-19 crisis using its circular city model. In this model waste and pollution are designed out, products and materials are kept in use for as long as possible, and natural resources are regenerated. This is facilitated by adopting open and smarter approaches to managing scarce raw materials, production and consumption, and creating more green and equitable jobs.

The circular economy cannot happen effectively without an open approach at its core.

Another example of this is captured by OpenUK’s Blueprint for a Carbon Negative Data Centre “Patchwork Kilt” which will be presented at COP26.

In response to the ICT industry’s emissions problem (doubling from 4% of global GHG emissions today to 8% in 2025 according to Shift Project), the Blueprint outlines how wholly circular, edge-based, carbon negative, data centres based on the Three Opens of technology (software, hardware, data), can lead to 80% decarbonization and 90% dematerialisation.

A final word on transparency and the enabling role of open data. The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals set an ambitious agenda for progress on the world’s most challenging problems by 2030.

With a problem set this broad, complex and requiring urgent action, open data needs to become the universal approach to enable transparency, measure progress and help achieve the SDGs.

“The more advanced users and enterprises, who are pushing the boundaries, get involved because they want to be able to influence the roadmap, and be part of the community to make sure that the projects are healthy and long lived, and so that they can continue to rely on them. It’s that ‘rising tide floats all the boats’ scenario. There is a little bit of prisoner’s di-lemma too: I have to be involved, because if I wasn’t, my competitors would be in control. But it all works out to the good.”

Liz Rice, Chief Open Source Officer at Isovalent & Chair, Technical Oversight Committee at CNCF and OpenUK Ambassador

Opening Up the UK Energy Sector

Gavin Starks, CEO, Icebreaker One

Gavin Starks, CEO, Icebreaker One

Improved access to energy data is at the heart of the UK’s journey to a healthy, growing net-zero economy. This will have an impact not only on the energy sector but also across transport, water, agriculture and the built world.

This is essential to the energy transition the UK must now make—both to meet its Nationally Determined Contributions and to deliver the government’s plan for a green industrial revolution. A functional open web of energy data is an essential piece of national data infrastructure: as important as our roads, rail, water and broadband networks.

Developed with government support, the Open Energy Programme is an emerging, tangible success story that addresses this challenge: a non-profit service that makes it easy to search, access and securely share energy data (for both open data and shared/commercial data). It will unlock access to data held by thousands of organisations and institutions to enable an open marketplace and our net-zero future.

Its work supports UK National Strategies including the Industrial Strategy, National Data and Digitalisation strategies, the climate agenda, the investment community (e.g. FCA/PRA Climate Financial Risk Forum) and the UK’s international leadership around energy and climate (UK is leading the Global Mission Innovation on Energy Data Interoperability as part of the Paris Agreement).

Through open collaboration and open standards, organisations across the UK can unlock sector-wide efficiency and innovation that can enable their own data and technology strategies. It will radically reduce the cost of data sharing and transform access to data by creating cohesion and interoperability: competition should focus on impact, not the rules of the game.

For example, as millions of smart sensors come to market (e.g. in smart meters, heat pumps and electric vehicles) we need to ensure that data can be shared securely and safely, with minimal cost and friction to both operators and innovators. Intervention is needed to address the priorities of resilience and innovation: from enabling double-digit improvements in retrofit efficiency to demand response to better balancing of decentralised flexibility markets.

BEIS, Innovate UK and Ofgem have been supporting the development of Open Energy and other solutions that make data more open and accessible and using a more open infrastructure.

Making this a success requires a mix of interventions: policy leadership, convening industry and infrastructure development— the UK is at the cutting edge of open innovation.

Opening Up the UK Energy Sector

Laura Sandys CBE, UK Government Energy Sector Digitalisation Task Force Lead

Laura Sandys CBE, UK Government Energy Sector Digitalisation Task Force Lead

Decarbonisation has changed the whole shape of the energy sector, digitalisation is going to be absolutely crucial. And I think there is a much greater and growing realisation of this. There is an appreciation of this and there is enthusiasm.

An EV car for example, can do two, possibly three things. It can consume energy, it can dispense energy, and it can store energy. That’s three functions per EV car. You then multiply that with solar panels, heat pumps, new technologies, this system is moving really from, a few to millions and millions and millions of actions and assets. And how is that going to happen? It’s certainly not going to happen in an analog way.

Digitalisation is not a charming add on, it is absolutely essential to the whole system operating.

The culture of the energy sector is certainly not open. We went some way with the data taskforce to talk about presumed open. We had this triage process, which allowed people to close things that needed to be closed, but only with the presumption that everything should be as open as possible. You layer on to that open source. And you can start to see quite a clear trajectory, from presumed open data to open source software.

It’s still one step at a time, although I think the digitalization taskforce will push this quite hard, but to do it we must have what I would call some core plumbing across the system.

Our job in the task force is to create the very basic plumbing that allows all these exciting tools to layer on top and that is where open source becomes important to allow you to put your whizzy digitalisation structure on top, but to allow interoperable, interrelated systems.

The only way you’re going to be able to do this is through opening up how and what you’re utilising to make those connections work.

One of the other key areas that’s really important in energy is security and stability. And we’re very keen to reverse the mentality about visibility. So visibility is seen as very frightening. And actually visibility is actually crucial. So everything is about being as open as possible with the understanding that this is critical national infrastructure and this allows one to start to look at openness in its widest sense.

Some people already understand exactly what we’re talking about, but other people are just starting to understand and I think there’s an education job, on what open source is and where it’s appropriate in infrastructure for energy and beyond. The Energy Digitslisation Task Force is going to be reporting back to the Government on this governance framework on its pillars, and there needs to be an understanding of open source software.

The opportunity for the UK energy sector is transformation optimisation, it’s really absolutely crucial to net zero.

Case Studies in Energy

Icebreaker one

Prioritising open for positive change

In conversation with Gavin Starks, Founder and CEO

About Icebreaker One

Announced at Davos in 2020, Icebreaker One brings together data sources and users to facilitate reaching net zero carbon emissions. Open-source software and open data are critical to the solution. Gavin Starks, Founder and CEO, brings a unique perspective to Icebreaker One. His open-source roots go back to the origins of the World Wide Web itself, and he has decades of experience in the establishment of common data infrastructure standards, most notably in setting the foundations for Open Banking in the UK and as founding CEO of the Open Data Institute. We spoke to him to find out more about why Icebreaker One adopts an open source approach, and why others should do the same in energy.

Open source and sustainability

Open source is embedded in the very fabric of the organisation and its sustainability mission. Gavin stresses, “Everything we’re doing uses copious amounts of open source software.” Everything we produce is also published as open by default on their websites and services such as Github.

Imagine a decision-maker could mandate net-zero, continuously measure progress and act to adapt incentives in a timely, credible manner. The data required to give force to leadership mandates for climate-friendly policies and targets is likely to grow exponentially in the near future and open source can help. Icebreaker One’s own procurement processes include criteria devoted to commitments not only to net zero and to open licensing.

Part of how open is used to instrument net-zero is seen in the development of open standards – frameworks for robust and secure environmental and financial data sharing that can help organisations to understand how best to use data as a continuous flow of evidence that informs positive action.

Open source: Hardwired into Icebreaker One

Whenever possible, open source software is used at Icebreaker One. There’s no need for a transition from a closed to an open model for Icebreaker, as open has been their aim from its inception. This is reflected in their employees; Gavin notes that “the people who are attracted to work with us are already using open source software…and if they’re not they get there pretty quickly.” They actively seek opportunities to promote its use, and believe that commercial pressure will help continue this trend more widely.

Developers in the team can use company time to devote to updating open source software projects used within the organisation. Gavin explains that, “We effectively help pay for our team to contribute back to open source projects”. It’s through this mentality that there can be financial incentive to work both with open source software and on open source projects which will help drive the entire open ecosystem.

Time for idealism to meet practicalities: there are clear incentives for open source

The solution? For open technology, open data and open source software to be able to provide adequate solutions for business, the compensation and value exchanges involved in open development need to be rewarded. To preserve transparency, enable people to build on each others’ work and develop solutions that work for everyone is in all our interests and, given the urgency of the climate issue, doubly so.

One risk in the development of open source solutions where there are no financial means of support creates a reliance on free contributions. While this has huge benefits in removing conflicts of interest, it’s not always realistic to expect individuals to continue. As others reap financial rewards from open projects there is a responsibility on them to play-it-forward and help employ or fund their ongoing development.

Value exchange needs to be reciprocal and developers have bills too. If your company is using open source software (and it is likely you are) why wouldn’t you unlock your team to devote time (even a day a month) to help support them — this benefits your own business.

Scottish Power

The opportunity open source software brings for digital transformation and sustainability

In conversation with Douglas Smith, Director Digital, Innovation & Transformation Director

About ScottishPower

ScottishPower is the first integrated energy company in the UK to generate 100% green electricity. It’s part of the Iberdrola Group, one of the world’s largest integrated utility companies and a world leader in wind energy. They recently established a brand new digital services capability in the IT function to allow the company to keep pace with the broader digital transformation happening in the energy sector. Open source will continue to play a role in the future of engineering at ScottishPower. When it comes to internal engineering, open source software (notably Java platforms) is already used throughout their architectural footprint.

Open source as part of a broader upskill

ScottishPower are investing heavily in upskilling their employees. Educational tools found on online learning platforms are being deployed including open source software content, such as Python, which is used extensively across the company. The need for IT proficiency throughout the organisation will only increase further.

Douglas explains that “the boundaries of IT are becoming very blurred…many more people in the organisation will be engineering software in the future in comparison to what happens today and used to happen”. Citizen data scientists, for ex-ample, are already using Python to develop their latest models.

Going forward sustainably: open source as part of the solution

Douglas believes that demonstrating the sustainability credentials of open source software could be a distinctive point of reference and encourage more organisations to adopt it as part of a green decision making mindset.

Douglas explains: “If you can turn open source software into the most sustainable set of software that any organisation should be running, this will play to a priority that every corporate organisation is going to have to walk through in the future”. Open source can be part of the net-zero solution for companies going forward, in part by harnessing the communities’ enthusiasm for driving energy efficiency solutions and also by its very reusable nature.

As we move towards a green future, open source’s relationship with sustainability needs to be addressed further in order for it to reach its full potential.

ZTP

Open source, sustainability, and energy software consultancy

In conversation with Alex Hill, Managing Director

About ZTP

ZTP was established in 2012 as an energy consultancy brokerage to support energy consumers to trace their consumption. It brings together in-house expertise and technological innovations to deliver integrated systems and solutions.

Open source: reshaping sustainability agendas

ZTP recently developed two energy management portals called trace, and Kiveev using open source software and languages, including MySQL, Django and PHP. They felt that these platforms could not have been built without the use of open source software.

Moving forward, they plan on building an internal portal that allows them to combine Energy Performance Certificates (EPC’s) to standardise the available data. Since 2009, all commercial real estate has had to have an Energy Performance Certificate, (EPC). In order to buy or sell property, the EPC rating must be shown to be above a certain level, which demonstrates and promotes a more sustainable environment. Businesses need transparency and access to existing reports and EPC’s which the ZTP platforms facilitate. The use of open source software and open APIs improve the ability for businesses to identify their buildings EPC ratings in order to sell, let and capitalise on their properties. The use of this open source software is facilitating these efforts within the energy sector. As Alex says: “currently businesses can’t make those sorts of connections unless they have a full database of all the EPCs for all the sites they own.”

Through developing these open API’s, businesses can help drive change in the private sector market by allowing investors to more readily identify profitable buildings as opposed to ones which are redundant due to their poor sustainability ratings, and thus indirectly encourage remedial works by their owners. ZTP plans to leverage the benefit of their open API by using it to cross reference their clients’ building data. This open-minded vision is made possible by the skill set of their employees.

Open source skills

At ZTP, proficiency in open source software has become essential to the company and this has been reflected in their recent hiring of three software developers. “For Trace,” Alex explains, “the developers needed to have exposure and experience in Python and Django as a language and a framework”, for the Kiveev team, they needed experience in PHP and or ZTP’s database a working knowledge of MySQL is vital.

Community and open source

Open source can open doors. But it also keeps them open. It creates a positive reinforcement loop.

Alex notes that a significant benefit of open source software within ZTP is the collaborative nature of the communities associated with the languages and tools they use and how those communities’ interaction contributes to their maintenance and ensures that they are sustained on an ongoing basis. They see this sitting in opposition to the natural product lifecycle dictated by a proprietary code.

Without open source, Alex emphasises, “we wouldn’t really have had a business”. For ZTP, the benefits and opportunities that open source brings to them as a business are clear and they expect that this will increase in the future. But in this case, doesn’t just bring a business benefit. Their use of open source for platforms that improve EPC’s in turn improves sustainability within the overall energy sector.

Healthcare Case Studies

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health

Innovating in children’s healthcare

In conversation with Dr Simon Chapman, Acute Consultant Paediatrician and leader of the Digital

Growth Chart project for The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH)

About RCPCH

The RCPCH takes a holistic view of patient health and wellbeing, representing clinicians who work across the care of babies, children and adolescents. They provide career support for their members, as well as leadership and advocacy to government and the health authorities, and a range of programmes to improve child health. Recently they launched a digital version of the growth charts which are familiar to British parents as core elements of the Red Book, using open source to accurately calculate centiles for a child’s height, weight, BMI and head circumference.

Seeing an opportunity: the context for Digital Growth Charts API

Although we often think of the NHS as a single entity, its organisation and governance are relatively federated, and the IT systems which support it are themselves fragmented. The majority of services are provided by a handful of large providers such as Epic and Cerner, who offer a range of electronic healthcare record (EHR) packages. However, there are specific use cases – such as an accurate digital growth curve tool – where this market structure does not naturally support commercial development as it would – for instance – in A&E triage and processing. Simon and his colleagues represent an intriguing type of open source entrepreneur – the expert clinician and coder.

Open source in action

By embracing open source, the RCPCH[1] has been able to make faster progress in modernising the underlying thinking for this important diagnostic tool. The team’s ways of working have been agile and over the last 18 months they have gone from just a concept to MVP to a stabilised service for customers whereby accurate assessments of growth against normalised standards are delivered straight to the user and can be easily integrated into other interfaces simply and cheaply.

The team uses GitHub to house their repositories, of which they have seven. A repository allows for dynamic conversation which can be scrutinized more thoroughly as every decision is made publicly. Different bits of code are tied to a single slot that is pasted in Kanban boards. Simon observes “this is the first time I’ve really seen the value of open source software”.

Digital Growth Charts API in practice: challenges and opportunities

The valuable characteristics of this open source software project have been about transparency as much as enlisting help through collaboration. Simon explains that, like him, a number of clinicians have been able to contribute to parts of the project alongside their full-time work precisely because of the open source model he and his colleagues have employed. A further enabler for this specific, single-use case approach in terms of medical data is that the tool does not require the storage of patient data – it is at heart a piece of code to act as a sophisticated calculator.

Conclusion: just the beginning

The Digital Growth Charts API is exciting, and it’s just the beginning.

Its combination of open source software development, agile management and an API hosted by a trusted intermediary is why Simon claims that “[this] could be game changing”. This active encouragement of clinicians themselves being involved and understanding (at least in part) the process means whatever is being created is fit for purpose. Open source software has been instrumental in paving the way for further innovation.

NHSX

Building confidence in open source solutions

In conversation with Andrew Harding, Open Tech Lead

About NHSX

Founded in 2019, NHSX, a joint unit of NHS England and the Department of Health and Social Care, supports efforts to digitise services and transform how the UK health sector leverages technology for seamless patient experiences. Developing open source software and code to help do this, NHSX leads digital transformation through products, policy and standards.

Value alignment: Open source and NHSX

Andrew Harding, Open Tech Lead, believes open source software is “where we want to be”, allowing stakeholders to share ideas, solve problems, compare solutions, iterate and amend, while decreasing the burden of development and “making more use of the work we do in house.” Through knowledge sharing, NHSX creates solutions that work across multiple trusts; a step towards solving the problem of interoperability and avoiding lock in.

They’ve open-sourced both Covid apps, the new ‘Admit Me’, ‘Data Lens’ and ‘Long Stayer’ tools, and more are yet to come.

With the use of open source software comes a need for creating adequate and uniform standards as well as best practices within the healthcare sector, especially when it comes to licensing and copyright. As Andrew says, “What we’re trying to get to is a shared culture, shared standards. And through those shared standards, a system that works better and more efficiently for patients.”

Since its inception two years ago, there’s been a movement within NHSX to increase open policy development and best practices for open source software.

Confidence and Trust

Andrew believes that if we want to see usage and adoption of open source increase, we need to build trust in its value and build the confidence of both users and engineers in its deployment. He sees that one way to build trust is through centralised policy: “If I can say to workers across the NHS, here are the licenses you can use, here are routes to success that other people across the system have used, here’s your best practices, our GitHub policies… if I can give them all of those tools, then they can go to their own local IT teams, their Boards, they can go to anyone who has authority over how they do business locally and say, “Look, we’ve got a mandate, we’ve got permission, we’ve got national commitments in the new Data Strategy, we’ve got specifically written policy and guidance on how to make this work.”

This goes hand in hand with enabling enthusiasm, education and the confidence to use the tools. Investing the time, energy and resources in supporting those people who can be easily encouraged to use open source software is a critical step forward.

Healthcare: a glimpse ahead

The healthcare sector has a lot of will and desire to make things more open, more accessible, more shareable and although there is a lot of distance to be covered, it is on the right path. As Andrew sums it up, “The NHS has over 120 GitHub repositories, and thousands of analysts across our institutions, many unfortunately in silos. Open ways of working enable them to collaborate, increase efficiency, reduce repetition, and ultimately lead to better outcomes for patients. It’s a clear win.”

Mindwave Ventures

Making the case for open source in digital healthcare

In conversation with Kumar Jacob, Founder and Executive Director, Mindwave Ventures

About Mindwave Ventures

Mindwave Ventures was established to improve the user experience in digital healthcare. It’s one of the leading, NHS approved, Personal Health Record (PHR)/Patient Portal developers in the UK, working with more than eight Trusts. Mindwave’s PHR, Maia, collates a patient’s health information into an easily manageable portal.

Open source software in Mindwave: PHRs

Maia is built as a modular platform, meaning its modules can be easily shared or swapped. It forms a repeatable foundation for each additional implementation. It is available as open source software, thus making it cost effective for new NHS organisations. Using open source software, PHR’s are developed for NHS organisations, taking into account their localised requirements, clinical services and desired user experience.

Software developers at Mindwave rely on open source software. For example, for their front end development they are increasingly using Reactjs and all of their databases are on Postgres. Kumar notes that using open source software enables developers at Mindwave to “learn and improve as [we] go along”. Part of the beauty of creating Maia using open source software is that code can continue to be developed iteratively.

Open source: maximising efficiency

When a new variation of PHR is created for an NHS organisation, modifications that may suit a previously established one can be incorporated at very little additional cost. Using open source software allows for the creation of customised solutions for each trust building on the work done for others. Instead of creating things as a single entity, using open source to build in a modular way makes it easy to reuse – therefore increasing efficiency. Kumar sees using open source as a no-brainer: “as soon as you’re reusing 60-80%, it’s obvious that open source should be your favoured option”.

Going forward: why open source makes sense for the future of digital healthcare Kumar thinks that it’s important to use open source to facilitate collaboration. This, in turn, promotes ongoing development in the digital healthcare space. “Otherwise,” Kumar stresses, “we are going to end up with a cluster of applications all doing the same thing.

What’s the point of having ten different flavours of PHRs that are incomtible when an eco-system can be developed?” It was possible to make Maia into a product as its previous iterations were developed as open source. Kumar explains that “underneath, all the same base code was used and set up as open source. We can take the best of everything and refresh and modernise it and make it available newer clients”. In a fast moving, increasingly digital world, using open source in order to customise offerings, will help drive innovative, scalable and affordable digital transformation in healthcare.

Digital Health and Care Wales

Third-party support enabling open source to thrive

In conversation with Paul Owen, senior product specialist Corporate Applications

About DHCW

Digital Health and Care Wales (DHCW) are responsible for the digital transformation efforts for healthcare in Wales and delivering programmes to facilitate modern technology-enabled healthcare. One such programme is the expansion of digital patient records by creating a world-leading national data resource.

This is no mean feat; the Welsh NHS is made up of hundreds of legacy applications that are not connected. DHCW’s task of centralising these systems has been made considerably easier through their use of open source software.

DHCW is a special health authority within the NHS who design and create corporate, digital and patient facing applications. They use open source software solution Apache Solr in a clinical setting at DHCW.

Apache Solr

Solr provides distributed indexing, replication and load-balanced querying, centralised configuration, automated failover and recovery… and more. The implementation at DHCW is impressive: there are eight servers divided into four nodes – meaning there are 32 nodes served with upwards of 20 million documents.

As Paul notes, Solr is “quite challenging to learn…it takes a good few months to get your head around all the different moving parts”. The success of Solr at DHCW comes from the extensive support and learning they received through its implementation and ongoing use, with its value including both collaboration and skills development in its use.

Using open source with confidence: third-party support and consultation

Paul explains that due diligence is paramount when incorporating new technologies and this is particularly so in healthcare. Solr, like any other product, had to be approved as complying with their internal processes. In this instance they worked with a third party consultant and support service, OpenSource Connections to give DHCW the confidence to use the application. Solr could be implemented with assurance that they had the support behind them for it to function effectively and in tandem with learning and skills development internally to be able to maintain it going forward.

Adapting open source to suit DHCW

The Corporate Application team have become so well versed in Solr that they have been able to implement their own alternative instances of the application for different areas of their business. They have used a smaller implementation of Solr to index other websites for the Welsh NHS organisation. This is one of the true values to the NHS in using open source software, the ability to freely scale and replicate.

Conclusion

When it comes to clinical applications dealing with sensitive information, security, reliability and support are fundamental. The question asked is always “what’s the best tool for the job?” Ultimately, Paul stresses that with the confidence garnered from initial third party support similar to proprietary software, open source tools by their openness offer the ability to learn and self support over time and so are often the best solution.

Increasingly open source software solutions are the most viable, cheaper alternative to proprietary software with the added value of skills development and the ability to reuse and recycle. In a healthcare environment, where speed of access to documents is crucial to providing the best care, open source is becoming increasingly important to developing efficient systems. It’s an exciting time to be incorporating open source within the healthcare sector.

Acknowledgements

The research was led by Dr Jennifer Barth, Research Director at Smoothmedia Consulting Ltd in partnership with OpenUK in 2021. The independent team of economists, psychologists, data scientists and social scientists included Areej Ahsan and Emily Naylor.

Phase Three is sponsored by GitHub. OpenUK has a large number of financial and in kind supporters to all of whom it is grateful and the following major supporters Arm, Google, Huawei, Microsoft and Red Hat, without whom OpenUK’s work would not be possible.

Thanks for their contributions to our Creative Director and graphic designer, Georgia Cooke, Web developer Elefteria Kokkinia at Civic and Chief of Staff, May Cheung.

We are grateful to the large group of contributors to our workshops from many companies and foundations, all of whom are working on reporting and economics of open source software and who will continue to meet quarterly to evolve this research.

They are too many to list but know who they are.

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world: indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

Margaret Mead, anthropologist

Methodology

The research used a mixed method approach to explore and demonstrate the value and values of open source software in the UK.