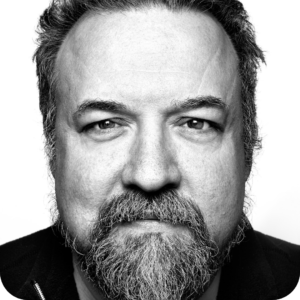

A Fireside Chat: Chris DiBona,

Senior Associate Fellow for Cyber Security Research, RUSI

State of Open: The UK in 2024

Phase Two: The Open Manifesto Report

Fireside Chat: Open Source Program Offices (OSPO)

Your background in open source

I was attending George Mason University in Virginia, and the Sun Microsystems lab was small, hot and crowded. One would often have to wait until late at night to use a workstation directly and I would often find myself telnetting in from home. In 1995 I picked up a walnut creek cdrom which had slackware Linux on it which I installed on a machine I had at home. I would go so far as to trade some computer manuals for a AT&T 3b1 machine because it was a ‘real’ unix. I remember struggling to install the gnu-tools on it, when I realised that the Linux machine I was doing all the prep on was a zillion times better than the ancient yellowing plastic workstation.

I fell in love with Linux and Gnu and all I could do with it. Later I’d move to California and take an active role in growing our local linux users group. That would lead to a job at VA Linux (then VA Research).

Can you give us context on Open Source Program Offices?

The term OSPO came about pretty naturally. I had worked at the US Department of State in Washington, DC before heading to California and it was absolutely littered with ‘program offices’ . So shortly after Christine Peterson coined the term I changed the name of my then quite small group to the Open Source Programs Office.

I should point out that no one can really claim credit for coining the term. Program offices have been present in the US since before world war II. Adding open source to it isn’t a big achievement and I’d imagine others did the same independent of our doing so at VA.

OSPO’s became a kind of catchall, so maybe I’ll talk about my OSPOs over the years.

The Google OSPO started simply. My goal was to bring Google’s products into compliance with the various licences expressed in shipping products. As part of that, I wanted to give a golden path for developers at the firm to release patches and projects to the outside world. It had been haphazard to that point. That necessitated launching a centralised developer relations function which Google hadn’t had before. This led to releasing new projects from Google into open source, our joining of industry consortia like the Linux Foundation, recognising our membership in the ACM and the like. Prior to Google, I spent a fair amount of time explaining open source and free software to a variety of audiences and at Google I would continue to do that and then expand beyond into topics central to Google’s needs, like search, later Android, Chrome and the rest.

The OSPO at Google was about being an effective bureaucracy for intake and release of software first, by the time I left in 2023, we were releasing about 6 projects a day on average and innumerable patches to existing projects. For ‘bigger deal’ projects like chrome and android we would often help them start and come in for detail work that their developer relations groups would need help with. We ran the android open source projects infrastructure for quite some time, as an example.

As time would go on, we would take on a variety of unusual roles at the company, beyond the open source world, into running .orgs engineering teams, helping google ideas, etc.. but that was more about helping where we were needed and less about open source’s applicability to those groups.

OSPOs are inherently different depending on the company they exist at, sometimes they report to legal, sometimes marketing, sometimes product, or the CTO or distributed among them all. What matters is that they serve the organisation effectively. One thing common to them all is they act as a knowledge base for the larger firm. The best offices are in service to the firms they work for , and act as the friendly interface for the outside open source developers they depend on.

Thinking of the UK’s public sector shift to an open source first policy under David Cameron in 2010, do you have any thoughts on open source in the UK?

I remember talking with the UK Digital Service about this at the time. When I speak with governments about open source it almost always becomes a discussion of up-skilling domestic developers, and trying to leapfrog technologies, or trying to maintain digital sovereignty and not become too dependent on foreign powers for their IT infrastructure. That hasn’t changed.

With respect to public sector usage, it’s … slow. The adoption of open source directly isn’t really a thing, but the providers of IT solutions to governments and militaries are *avid* adopters of open source. So sometimes the discussion is how contractors can work with open source developers and what it means to count on projects which may not be under their control.

We’ve all seen groups get upset because an open source developer goes a different way, but that’s part of the deal, so helping them understand the inputs and outputs of these projects is fundamental.

Governments around the world have shifted to having OSPOs – how would you see the role of a government OSPO as including this legislative support?

It seems a shame the EU’s OSPO were unable to influence the CRA to help dull its impact on open source developers. EU Policymakers I’ve spoken with generally don’t want to hurt their open source developers, or even non-european oss developers. Yet they produced a bill and Act that has the potential to do so.

Sometimes the job of open source advocates is to help clean up a law after it’s been passed. I had to do a lot of work to help developers running afoul of ‘subsection c’ of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act some time ago, and people like us, with these skills will need to help the EU come to terms with the unintended consequences of the CRA.

Thinking across OSPOS why do you believe OSPOs were so hard hit in the tech sector cut back?

I think when companies go through a cost cutting exercise, they look for things to cut and not get hurt by cutting in the short term. OSPOs were hit, testing groups were hit, marketing groups were hit,engineers were made redundant, sales people were let go. That’s the nature of a layoff. They are always and by law about cost cutting.

Where do you see the future of the OSPO?

Considering a nation-state ospo, I have to think that the utility of having an organisation who can help the various ministries take best advantage of, and work with, open source developers is needed. If for no other reason to keep the UK informed on who they are depending on for the functioning of the nation. We all know that the world depends on open source, so understanding it and acting on that fact seem paramount.

I consider a modern ospo to be a facilitator and strategic resource more than a gatekeeper on the critical path to adoption. I think that ospos that think like the latter are , well, obsolete, and a modern ospo is a force multiplier for its organisation.

How do you see the impact of AI on OSPOs?

When considering the use of RAGs and LLMs in the sciences and in applied engineering fields, I have to say I have not been this excited in decades. It’s so much fun and so insanely productive to work alongside tools like copilot and chatgpt and local implementations of models like Mixtral’s 7b that I can only say I’m so excited for the future of software development. When I speak with colleagues in the legal field about their use of legal oriented LLMs I find similar excitement. It really reminds me of my early days in open source , it’s like being granted superpowers. It’s not perfect of course, but it’s such a great starting point for any engineer, developer or technical writer.

Final words

So since my days as a civil servant, I’ve always seen government employees as extremely idealistic and deeply committed to serving their public. So that in mind, the public sector underuses open source, and IT in general, and I think it’s because no one is there to help them do so, help them see how computers can help them do their jobs more effectively and serve their citizens well. A government digital service could be a big help there, and I hope that’s the direction that governments worldwide embrace.

First published by OpenUK in 2024 as part of State of Open: The UK in 2024 Phase Two “The Open Manifesto”

© OpenUK 2024 ![]()