These are live-captured notes from the talk OpenUK CEO Amanda Brock gave on 12th February 2021, as part of the Future Leaders series.

Amanda joined Canonical, the commercial sponsor of Ubuntu, 13 years ago on the day of the talk. She was meant to leave after a few months to join Amazon. Within six weeks she knew she was staying — she’d fallen for open source. Joining as their General Counsel and setting up their legal team was an incredible experience.

In 2008, the idea that open source is not a business model was being promoted by Matthew Aslett, based on research into multiple companies exploring commercialising open source. Open source is a licensing scheme and a method of creating software. It has to comply with the OSD — open source definition — but it is not a business model. Before you open source your code, you need to work out what your business model will be. Here’s why.

The Open Source What Ifs…

Brock was working with Mark Shuttleworth the founder on cloud. He explained in an Open Source Underdogs podcast that Open Source inherently means that you enable your competitors with your own innovation. This can be both emotionally and financially draining. This became an important understading to Brock who when she left Canonical joined a firm of lawyers for a couple of years. She had a steady flow of people coming to her wanting to open their products.

Before she worked with them, she walked them through a series of “What Ifs”.

What if…:

- You create something core to your business, and you open source it and someone comes along, takes it and make their own product?

- What if they make a lot of money out of it?

- What if they make a lot more than you?

That was enough to put off many people from open sourcing their code which Brock thought was right if they did not feel comfortable with the possibility.

Exploring models that work

Back in 2008, Matthew Aslett identified a small number of models that worked in his provocatively named Open Source is not a business model, report including, support, subscription and engineering services.

While Brock was at Canonical, Red Hat was a major competitor for them. Ubuntu quickly took significant market share in cloud from Red Hat: you can have 70% plus of the market… without generating any revenue. Canonical was fighting Red Hat tooth and claw, taking market share by day but they were also building collaboration with them.

They were both involved with the Openstack Foundation. They were in co-opetition. This institutional infrastructure space is one where Open Source works beautifully, Brock suggested. They could collaborate, to drive the software forwards with many engineers from many companies having eyes on it, to the benefit of many.

Cloud and contributors

The norm in the industry is for individuals to contribute code in their own name. It’s not clear if they are paid or not — or by whom. The Roads and Bridges report started a discussion on that because clearly keeping developers paid is vital to keeping a thriving ecosystem — but Brock believes its dating now, as initiatives like Tidelift work to make sure maintainers are paid. Developers have a right to eat: nobody in Open Source is trying to say you don’t.

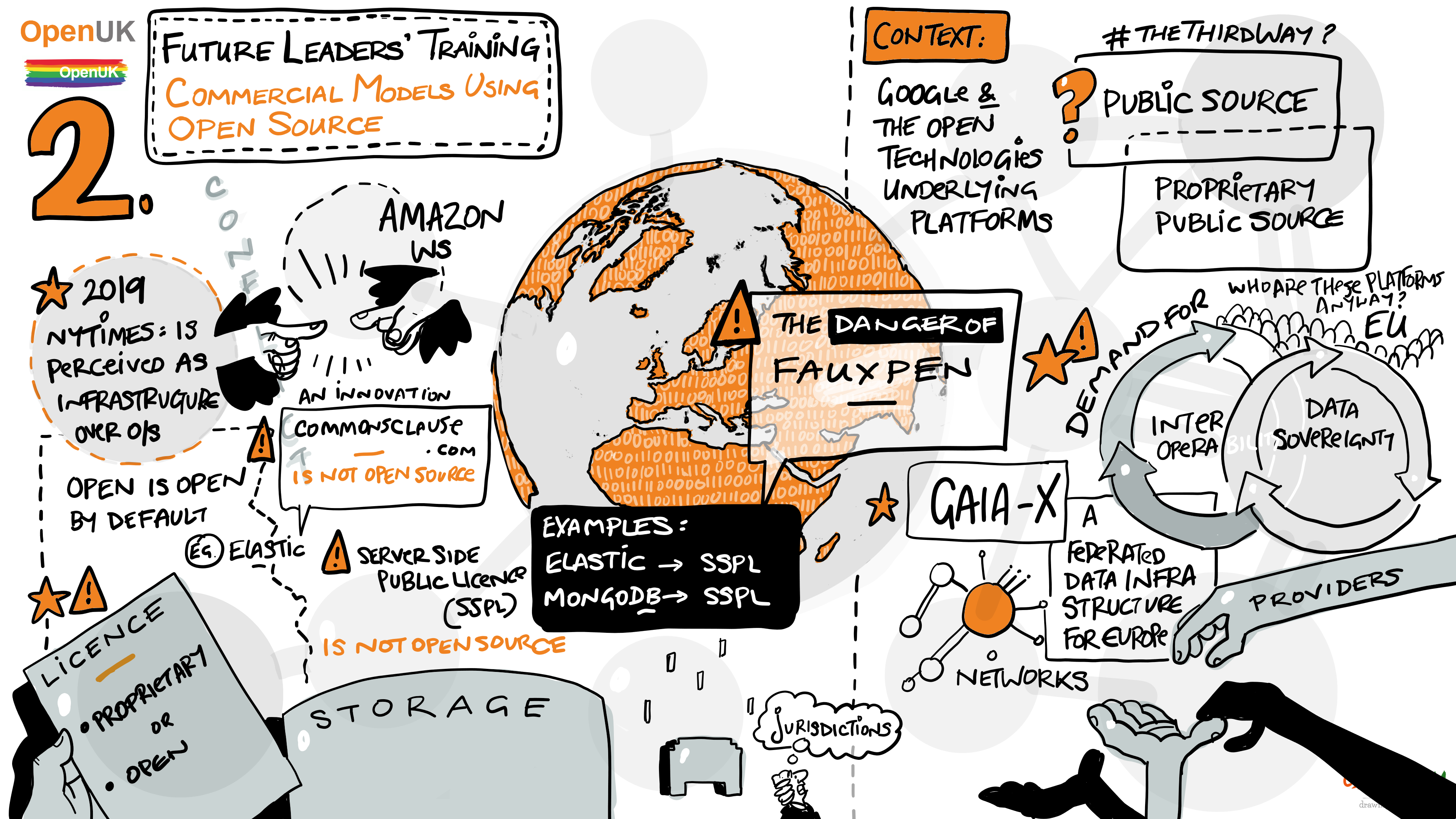

The emergence of the platform economy has really changed things. Brock guesses that 70 to 90% of the public cloud is built on open source. That cloud economy was powerful enough that 2019 the NYT published Prime Leverage: How Amazon wields power in the technology world. That article framed it as a platform issue, with companies whose technology was vital to the cloud behemoth being locked out at the profitable service layer. This is also where customers are locked in.

Amazon responded with a blog post by Andi Gutmans. He pointed out that there is no restriction in the licence stopping people doing this. He’s right. In fact, there can’t be. You cannot discriminate even if you are well-intentioned: that’s at the core of Open Source. Creative Commons has a non-commercial licence, and that leads some people to assume the same is true for code: but it’s not, at least not in the terms of Open Source.

One response was the CommonsCause: an add-on clause, creating restrictions on commercial usage. That is NOT open source, nor can it be under the OSD. Another response was the Server Side Public License (SSPL), but that’s another proprietary licence. Brock’s understanding, as a lawyer, is that licences are either proprietary or open. They cannot be “open-ish”.

Commons Claus and SSPL have caused confusion. Once your software moves off an Open Source licence, it is no longer Open Source. The OSI has been clear that SSPL is not an open source licence.

What are the solutions?

Things are moving on this, though. Platforms are acknowledging that it’s in their interest to keep the Open Source they rely on thriving. In April 2019, Google was already setting up a revenue-share scheme with open source companies. They are valuing the resources they are using. Similar deals are emerging with AWS.

There’s a recent piece in Computing talking about a possible third route. This is not new. There could be something between open source and proprietary, but it hasn’t been created yet. When the Open Source lawyers (several hundred of them) met in pre-pandemic times, they were not welcoming to the CommonsClause. However, some there were interested in Public Source or a third option: something that was like Open Source in that code was shared, but without an open source licence. She tends to call it Proprietary Public Source to clarify.

You can’t mess around with the OSD because so much depends on it and there are decades of historty. But you can look at a new model. If that needs to be built, well, it’s not Open Source, but it could possibly work but it will take a lot of time, expertise and investment to bring into existence.

Is there a fourth way?

Brock suggests that a fourth way may make this moot.

Regulators are starting to see the problems of data-lock in, both in terms of sustainability and also in compatibility. It’s hard to move between cloud providers.They are focusing on allowing citizens to own their data and concepts liek Data Sovereignty. It may be the next human right. They realise that it’s also fundamental to government and business modesl— and that’s where the pressure to open up will come.

She predicts that this will really start to happen this year and that the Cloud companies themselves will begin to open it up before any regulators get involved. And there are signs of that already: GAIA-X is a project to build a federated data infrastructure for Europe, for example.

Why does it matter?

Open is our future. Microsoft has come around on this. Satya Nadella’s view on Open Source is very different from Steve Ballmer’s. Their shift to cloud-focus and Azure means that they need to be part of Open Source. Also, a decade ago, customers didn’t ask for Open Source. Now they do. And they understand that all digital transition is also open source transition. And if you want the best developers — you need to let them work with Open Source.

Expect that as we continue to code, it will be collaborative — but don’t commit to Open Source for a business model until you understand how you will make money out of it and that everyone else can use it.